The Great Pacific Gyre – a whirlpool of discarded plastic refuse – is currently estimated to be as big as Texas. And the plastic bag is being fingered as a key component. But thanks to worldwide efforts, the scourge of the ocean may be slowing. By Jeremy Torr.

Singapore, April 8, 2017. If you nip to your local supermarket in Malaysia, you might get a surprise when the checkout operator asks you for your Unforgettable Plastic Bag – to scan. If your bag has a recycling barcode on it and the scanner recognises it, you will get a discount on your bill. It’s a powerful way to induce shoppers to reuse plastic bags (PBs), not just throw them away.

The plastic bag with a barcode. Discounts for recycling shoppers! Courtesy Tesco.

It is estimated that up to one trillion PBs are used around the world by shoppers and packers, but only about 10% are recycled. About half the rest ends up in landfill, and the rest ends up in trees, rivers, being burned (and producing toxic smoke) or in the ocean. Researchers say about 7 million tonnes of plastic ends up in the sea every year. It’s an astonishing figure, and a huge proportion of that is PBs. But bag users are starting to wake up to the dangers.

Squeezing the bag

Across the world, legislators, retailers and shoppers are all realising that action is needed against the ubiquitous PBs clogging our drains, gutters, rivers and oceans. Bags are poisoning the food chain too; even in distant, isolated Greenland, plastic has been found in the locally caught marine life, passed through small organisms and trawler feeders right up to whales.

Of the many countries that are taking action against the PB, it is impressive that it is not just first world eco-goodies that are taking a stand. One of the first countries to ban PBs was South Africa, which decided to outlaw them way back in 2003. On the back of an epidemic of litter disfiguring the countryside, it legislated for heavy fines and even jail terms for littering bag users. The problem in many less-developed countries is not heavyweight, re-usable bags, but the thin, single use bags that are used for selling drinks, food and small consumer goods from roadside stalls.

These are virtually unusable for anything else once emptied, and if thrown away often end up clogging waterways, being ingested by smaller fish and turtles that mistake the small torn fragments for food. Just as dangerously for the environment, the flimsy yet ever-present bags cause severe blockages in the basic drainage and sewer systems in developing countries, especially those that see monsoon rains every year.

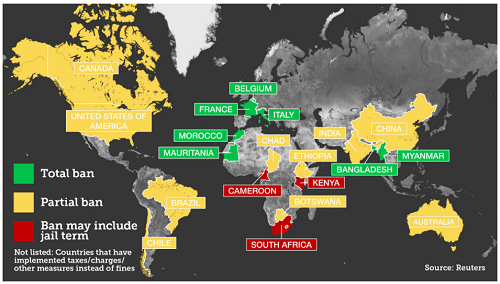

The chart below shows how countries are starting to legislate against PB usage; developing countries are taking a much firmer stand than first world consumer nations.

Bangladesh was the first nation in the world to legislate against PBs. The country banned them in its capital Dhaka way back in 2002. This went some way to reducing the estimated 9.5 million plastic bags dumped every day into the city’s gutters. Bangladeshi activist Hossain Shahriar said that only around 10% of those were disposed of – the rest “were the cause of increasing water born diseases, and air pollution-related environmental degradation from burning”, as well as potential flooding. The ban is still on the books, but is proving hard to enforce in a country of some 170 million people.

Every time you bring your bag to the supermarket you get a fishy discount . .

Many of the major supermarket chains and convenience stores in the Philippines have also dumped the PB in favour of paper bags – but many shoppers now bring their own bags in an effort to curb the offensive and toxic smoke that comes from burning PBs by the roadside. This happens because in many more remote townships there is no organised refuse collection. In the country’s capital, Manilla, some districts have also banned the use of disposable PBs and foam containers too – again to cut down the risk of blocked drainage systems as well as pollution. The city applied the ban in 2013, along with stiff fines for offenders. “We have already seen a lot of cases. We have issued a lot of tickets to shops and supermarkets,” said one environment protection officer.

In Kenya, the government decided that going to the source was the best approach. It banned the manufacture of PBs, as well as giving out and using them. It legislated to allow multi-thousand dollar fines to make sure users complied. The aim was to reduce litter and pollution, but also to help cut malaria – the discarded bags were identified as mini mosquito breeding ponds.

Indonesia has some of the worst beach litter problems in SE Asia. This one on Sumatra has astonishing amounts of plastic rubbish. Courtesy Jeremy Torr.

In China, the government banned free handout PBs in 2008. China’s National Development and Reform Commission said this cut usage by 66%; some 40 billion bags, but in many less developed rural areas many drains are still layered with plastic rubbish due mainly to lack of awareness of the problems.

Worst offenders

Although the most effective way to cut the encroachment of plastic bags is through education of users, some countries are working to recycle the notoriously difficult raw materials into something useful. In China, the use of plastic pyrolysis plants has been partially successful in breaking the PBs down into fuel oil, but the country’s success at this has seen a wave of imported first-world rubbish overwhelm its capacity.

As a result it has called a stop or dramatic reduction of millions of tons of imported plastic waste from the US, Australia, and the EU. The US alone ships almost 1.5 million tonnes of scrap plastics to China every year. And although the more developed countries are possibly more aware of environmental concerns, it seems they are less keen to make the PB go away, mostly for the sake of convenient shopping.

Even though the European Union had slated 2019 as the deadline for an 80% cut in PB usage, some are still lagging. France only banned single use bags, disposable plastic cups and plates in 2016. Back in 2002, Ireland introduced a PB tax, and saw a 90% drop in plastic bag and litter usage. However, its relatively affluent society soon got used to paying the extra, and the government had to raise the tax again in 2007 to keep the numbers down.

Embarrasingly, the US has no national legislation ban at all on single use PBs. It’s most progressive state, California, only banned them in 2014. New York City levies a small tax on every bag used there, but the country still produces millions of tons of plastic waste. And of that, only about 14% collected for recycling.

According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), this is way down on paper recycling (58%) and ferrous metal recycling (90%). The WEF estimates that 95% of plastic packaging material, worth over $80 billion a year, is lost to the economy down drains or into landfill.

"One bag reused is one less in the ocean" - Graham Drew

"We hope that the US [and other countries] can reduce and manage hazardous waste and other waste of its own, and take up more [of their] duties and obligations," said China Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying when referring to his country's clamp down on plastic waste imports.

Graham Drew, Creative Director of the company that came up with the barcoded Unforgettable PB idea, agrees. He said the idea was to help shoppers to re-use their bags, not throw them away. And he is optimistic about the issue.

“We believe more people will get into the habit of reusing bags. Every time [one] is brought back, it's one less in the ocean,” he said.