Is it possible the shale-oil boom has accidentally provided a solution to cutting greenhouse gas emissions? One company in Canada thinks it has. By James Teo.

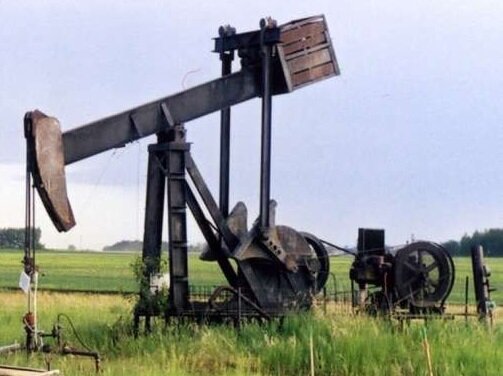

Alberta, Canada. March 2021. Canada’s Alberta province has lived off the back of oil and gas drilling since the 1850s. Latterly, as the resources deep underground have become more scarce and harder to locate, the red-hatted drillers have become ever more sophisticated in their ability to not just drill down, but also drill sideways, at an angle – to wherever the geologists think here might be a basin of oil or gas. But alongside the increasing skill of the drillers in winkling out ever more sources of petrochemicals, world opinion was changing. Gas and oil were seen as bad for the environment; contributing to carbon dioxide emissions and the build up of greenhouse gases. Wells were being abandoned almost as fast as they were being drilled.

John Redfern, Eavor CEO. Courtesy Eavor.

As far back as 2015, Albertan energy minister Marg McCuaig-Boyd saw the writing on the wall. She suggested that almost 80,000 abandoned wells – which at several kilometres deep into earth’s core often ran through rock up to 30deg C in temperature – could be used as heat pumps to help run greenhouse heaters, or even to turn turbines to provide power. It was a smart idea, which used a pump to circulate a special fluid in a closed loop between the bottom of the well and the surface, where the heat was then extracted to either heat a building or provide power. Better still, the cost of setting up the heat extractor loop would be only $100,000 or so, compared to twice that for a complete well decommissioning. But there was a fly in the ointment.

“This idea has never taken off because the amount of energy needed to pump the heated water to the surface … equates to 50% or more of the electricity the plant itself could generate,” says John Redfern, CEO of a new company called Eavor. Luckily, in 2017, even though all the smart drilling engineers couldn’t come up with a viable solution, a financial advisor asked a blindingly simple yet up-til-then unasked question.

“Why don’t we just use two wells and connect them horizontally below ground and on the surface to make a big loop — wouldn’t that flow better?” asked Paul Cairns, now Eavor’s business development officer.

“Luckily for us, Cairns wasn’t an engineer, he wasn’t a scientist, he was a finance guy, but a creative one,” explains Redfern. “He was unencumbered by geoengineering knowledge. This approach, he says, completely avoided the parasitic pump load that used so much of the power produced, and that made previous installations impractical.

The loop approach is much more efficient than a pumped well installation. Courtesy Eavor.

Redfern says he initially thought Cairns’s idea was “the dumbest idea I’d ever heard in my life… incredibly inefficient and capital intensive.” But then the company engineers took a second look at the idea.

They realised that if two wells could be joined in a loop, it would not only eliminate the parasitic pump load but would in fact pump itself thanks to a thermosiphon effect. This is where cold, dense water sinks down one well, heats up, then pushes heated water towards the surface – with no pumping required. Eavor-Loop™ was born.

The company has established a pilot project which has used that shale-drilling expertise to form an underground latticework of hot pipes to join two wells – one up, and one down. Using a circulating loop of special fluid, it harvests heat from deep in the earth that can be used for commercial heating applications or to generate electricity using conventional heat-exchangers and power generators.

The two wells, several kilometres deep, are linked by several kilometres-long horizontal wellbores – accurately drilled using some of that smart shale-drilling expertise. The bonus is that the working fluid is contained and isolated from the substrata, and much more environmentally friendly than an extractive, pump-based system. And because, thanks to the thermo-siphon effect, the fluid circulates naturally without requiring an external pump, it is hugely more efficient at extracting geothermal energy.

With tens of thousands of abandoned wells available, geothermal potential is huge. Courtesy Pinterest.

Initial results have seen the pilot generate easily scalable, always-on, industrial-scale electricity or heat to power the equivalent of 16,000 homes with a single installation. “Geothermal power (like this), if proven… and adopted widely, has the potential to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions compared to fossil fuel power generation,” asserts the Canadian government.

“We’re already seeing a lot of interest,” says Redfern, “Both oil companies and governments are taking a fresh look at geothermal as part of their overall strategy. (They) are thinking of it as a way to pivot some of their key assets and skillsets toward new clean energy sources, and as a tool and input to help “green” their hydrocarbon revenue streams,” he says.