Being able to visit natural spaces and parks is something most developed city-dwellers expect. But what if we turned our cities into parks in their own right? Daniel Raven-Ellison thinks most cities have plenty to offer as they are. By Jeremy Torr.

London, 29 October 2015- Having visited all of the UK’s national parks, photographer and naturalist Raven-Ellison says something is missing. An urban nature landscape. His suggestion is that instead of thinking that we have to travel to remote areas to enjoy nature, why not explore what nature has to offer in our cities? What if the planners made London a National Park City?

He bases his arguments on the UK, but his suggestion that most major cities contain a little bit of everything from meadows and hills to open spaces and wetlands applies to most of today's big cities. Raven-Ellison says most countries have specified inspirational and distinctive protected areas that all include every kind of major habitat apart from one – the landscape-scale urban habitat.

Eco-Diversity

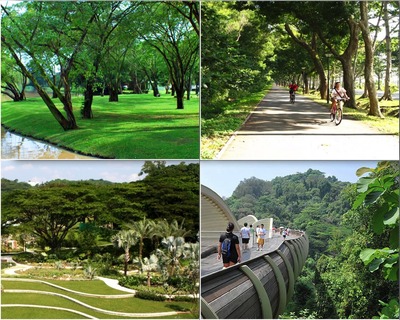

Open park spaces are tightly interwoven together to form a contiguous cover of urban greenery in Singapore. From anti-clockwise: Pasir Ris Park, East Coast Park, Hort Park, and Henderson Waves bridge linking Telok Blangah Hill Park and Mount Faber Park.He says the reality is that cities, our biggest urban habitats, can be more ecologically diverse and valuable than many parts of the surrounding countryside. They can also be equally good for outdoor adventures and, by their nature, be much more accessible and inclusive for all aspects of society. He notes that the Greater London sprawl (and possibly many other major cities) cover up to 10% of the entire land space of the country they are built in. Even more importantly, up to 80% of the population live in cities which means they are hotbeds of biodiversity by both resident and opportunistic flora and fauna.

Open park spaces are tightly interwoven together to form a contiguous cover of urban greenery in Singapore. From anti-clockwise: Pasir Ris Park, East Coast Park, Hort Park, and Henderson Waves bridge linking Telok Blangah Hill Park and Mount Faber Park.He says the reality is that cities, our biggest urban habitats, can be more ecologically diverse and valuable than many parts of the surrounding countryside. They can also be equally good for outdoor adventures and, by their nature, be much more accessible and inclusive for all aspects of society. He notes that the Greater London sprawl (and possibly many other major cities) cover up to 10% of the entire land space of the country they are built in. Even more importantly, up to 80% of the population live in cities which means they are hotbeds of biodiversity by both resident and opportunistic flora and fauna.

London is a great example, he says. It is well known as a financial, cultural and technological centre, but it is also one of the UK's biodiversity hotspots too. As well as being home to millions of homo sapiens, London boasts 8.3 million trees (Singapore, despite being a fraction of London's size has some 2 million) and 13,000 species of wildlife. Just under 50% of London's surface is physically green and it has 142 local nature reserves, 37 Sites of Special Scientific Interest and two National Nature Reserves.

But generally speaking, a city cannot be designated as a national park. It is usually classified as an area ‘outstanding for outdoor recreation’, ‘beautiful’ and ‘open-country’. Many cities have plenty of spaces like this, says Raven-Ellison, that pass the first two criteria of these three tests, but are not open-country.

"For me, the purpose of national parks is more interesting than how they are classified," he says. He says that usually, the purpose is to conserve and enhance natural beauty, wildlife and cultural heritage, and to promote the understanding and enjoyment of the special qualities of the national park by the public.

"But when looking to satisfy these requirement, National Park Authorities also have a duty to seek to foster the economic and social well-being of the communities they serve," he says. "This way of thinking about a landscape is extremely powerful - and one that many cities could benefit highly from."

Inspired by the city's landscape, there is a growing movement calling for London to be declared the world’s first National Park City. Supported by thousands of individuals, many organisations and politicians, the main driver is not that London should be thought about in the same way as England's national parks – but that planners should start using national park thinking in London itself.

This new kind of city-based national park would learn and take inspiration from existing national parks, but be distinctively different, says Raven-Ellison. Unlike rural national parks, a London National Park City would not have any formal powers prohibiting planning or development. Instead it would focus on helping residents and visitors to better understand and improve the environment and their enjoyment of it.

He cites the need to increase the number of children exploring, playing and learning outdoors as one of the greatest motivations for pushing for city national park developments. Indeed, one recent research paper from the UK revealed that as many as one in seven parents have not taken their child to play in a natural environment in the past year. Exact figures are not available for Singapore, but there is no doubt the figures would be high here too.

"We can act together to turn these figures around," says Raven-Ellison. "One of the aims of a National Park City would be to connect 100% of the resident children to nature. This would not only have positive effects on young people’s education, mental health and well-being, but no doubt increase how much they understand and value urban natural heritage, increasing the likelihood of them protecting and enjoying it not only on their doorstep, but in far more distant places too," he asserts.

Raven Ellison is convinced this approach would bring other benefits too. It would help to protect green space, improve the richness and connectivity of habitats, inspire new business activities, improve air quality, and foster a new shared identity for city dwellers.

"It is possible," he says. "All that is needed is for lots of people to join the movement by declaring their support."

Daniel Raven-Ellison is a ‘Guerrilla Geographer’based in London

For more info on City National Parks go to: www.nationalparkcity.london