What started out as a PhD investigating animal behaviour has transcended into a whole social approach to making a better life for elephants – and safer lives for the humans who live and farm near them. By James Gifford.

Anna Songhurst - looking to a holistic approach for the community, not just looking to animal welfare outcomes. Courtesy Ecoexist.

Botswana, July 2018. Dr Anna Songhurst has been studying elephants since 2004. During her PhD studies she was drawn to the growing conflict between humans and elephants in the Okavango Panhandle, Botswana. So she returned in 2012 to the Panhandle to set up an NGO, Ecoexist, with her husband, Dr Graham McCulloch and Dr Amanda Stronza, a US professor of anthropology.

In contrast with the rest of Africa, where elephant numbers have plummeted by 24% or 144,000 in ten years to 2016, Botswana has hundreds of thousands of elephants. The country's peaceful history, relative lack of poaching and huge swathes of wilderness have made it the region's safe haven, enticing between 130,000 and 200,000 elephants onto its land.

Some ivory poaching is happening, but more importantly, although 40% of the country's 600,370 sq.km. is protected status in the form of national parks or private concessions, over 70% of the elephant herds' range falls outside those areas.

Elephants have their own ancient routes - and they often cross human roads. Courtesy Ecoexist.

“You can't expect the largest contiguous elephant population in the world to stay inside protected areas,” Songhurst explains. “They have to be free-roaming and that is why Botswana is so unique. But the opportunity-cost to this freedom is the ensuing interaction with humans.”

“The peak conflict period is between March and June when the natural [water] pans dry out,” McCulloch elaborates. “In order to reach the permanent water in the south, the elephants must [navigate many villages] passing numerous appetising, crop-filled fields on the way.” Sometimes, it is not just the crops that suffer. Sometimes people are killed.

The consequences of elephants in village fields can be catastrophic. For many villagers subsistence farming is the only way to obtain food. Inevitably, retaliation is not uncommon. Elephants can be legally shot in Botswana if they are caught in the act, McCulloch says, with on average 20 elephants killed this way each year.

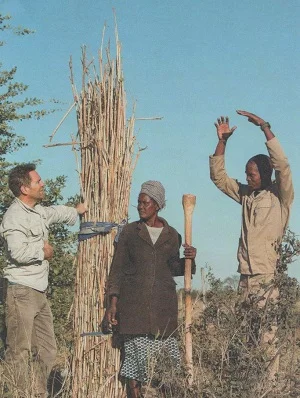

McCullogh talks to a local farmer about damage mitigation. Courtesy J. Gifford.

So the goal of their Ecoexist NGO is to address what Songhurst believes is the primary issue in conservation - human-wildlife conflict.

“Conflict arises from competition for the same resources - water, vegetation and space,” says McCulloch. According to local villagers, as recently as the 1960s elephants were rarely seen here. Then, after 1996, elephant numbers increased rapidly: by 2010, they had mushroomed to 10,000 and today around 18,000 elephants share 8,500 sq km with 16,000 people.

One element of the solution lies in the eight years of data Songhurst amassed during her PhD. The implications from such an extensive data set are vast but one empirical conclusion stands out: if a field is less than one kilometre from an identified elephant pathway, then it is twice as likely to be raided by elephants. As a result of their findings, new land allocations are being made only away from known 'elephant corridors’.

Just as important is their work on existing agricultural plots. The scientists describe how they adopted various techniques, one of which involved using chillies, which elephants dislike. By hanging cloths soaked in a mixture of crushed chillies and engine oil on their fields' fences, some African farmers have helped deter pachyderms.

Songhurst has been working with elephants since 2004. Courtesy J.Gifford.

“But given our remote location and proximity to the Okovango Delta, oil was neither easy to acquire nor environmentally friendly,” say the researchers. “So we adapted the method by mixing crushed chillies with elephant dung and water, then drying it in the sun to make briquettes. The farmers light these at night, which releases the capsaicin (chilli) odour as they smoulder.”

The modified technique requires a substantial investment in chillies - over 25kg for an average plot of 1-2 hectares - so Ecoexist set up community chilli plots, teaching villagers how to grow, nurture and protect them.

The idea snowballed. “When private farmers saw us buying chillies from community cooperatives, they started growing chillies as well, so we put them in touch with a local sauce manufacturer. Now they supply the manufacturer with high-grade produce, and keep the lower-grade chillies for dung briquettes, effectively creating a new cash crop,” said Songhurst.

Another approach the NGO takes is to help make farming more efficient using conservation agriculture (CA). New methods have increased yields by up to ten times, McCulloch asserts, “… enabling farmers to have smaller plots, which are cheaper to fence and easier to protect.”

In addition, rotating crops and using mulch – both new methods – obviate the need to frequently relocate fields: a necessity of traditional farming, due to the poor Kalahari soil. This in turn frees up more space for elephants. Despite the successes, not everybody wants to change their traditional practices.

“But [successful] converts to our approach often become our biggest advocates,” says Songhurst. Namo Mokgosi, an Ecoexist community officer, is a prime example. “I tell people not to shoot elephants as they bring value to our country. Things have changed; because of the mitigation techniques, shooting them is now a last resort instead of the first thing farmers do.”

In Botswana, elephant numbers are rising - so local people need to learn how to live with them. Courtesy J.Gifford.

Songhurst and McCulloch say they are trying to build an 'elephant economy' - a range of income-generating goods and services that stem from elephants that ensure the local community see value in the mammals. These range from drawings and sculptures sold in safari lodges, to specialised tourism activities such as a sleep-out decks overlooking elephant corridors. They have even created 'elephant-friendly' peanut butter, popcorn, and elephant-friendly beer.

So far demand has been limited, but they are targeting the 100+ safari lodges operating in northern Botswana, and have high hopes.

The scientists believe this holistic approach is integral to their success. 'If you really want to save wildlife, you have to better the lives of the people who live with the animals,” says McCulloch.

This story and most of the photos are from James Gifford, who originally published the account in the Royal Geographical Society’s Geographical Magazine. Gifford has just published a new book, Savute, which describes a remote and wild corner of Chobe National Park in Botswana. Gifford says Savute must rank as one of the most spectacularly enigmatic places in the region. It has a river that rarely flows, a marsh that metamorphoses from wasteland to watery paradise and, towering over them both, a parade of prehistoric hills. Within these habitats lies a complex web of wildlife whose fascinating tales are vividly brought to life in this book – a stunning visual journey that took two years to capture, and promises to delight, astonish and enthral.